Crying in young infants

Crying is normal physiological behaviour in young infants. At 6-8 weeks of age, a baby cries on average 2-3 hours per 24 hours up to 3 times per week.

Excessive crying is defined as crying >3 hours/day for >3 days/week. However, many babies present with lesser amounts of crying, as the parents perceive it as excessive. Excessive crying is often referred to as 'colic' but this is generally considered an out-dated term. The term colic is a descriptive term indicating the amount of crying. It is not a cause for crying nor does it indicate specific underlying pathology as the cause.

When a parent informs you that their baby is crying excessively this must be confirmed before directing management towards treatment of excessive crying.

There may be a mismatch between a parent's expectations of their baby’s crying and the reality of known newborn crying patterns.

Treatment will generally focus on parental education and support, strategies to help reduce crying, consideration of possible parental depression or anxiety and strategies to provide some R&R for the parent/s. View the 'Resources for parents' section of this resource.

Example questions

What does Jane mean when she says Michaela has been crying excessively for the last 4 days:

-

Has there been a sudden or gradual onset to the crying behaviour?

-

How long does Michaela cry for?

-

How often does Michaela cry?

-

Is there any pattern to her crying e.g. related to feeds or time of day?

-

Does there seem to be any particular trigger to the crying?

-

Does anything seem to make the crying better?

Example questions to take further history

-

Are there any associated symptoms e.g. vomiting, change in stools, blood in the stool?

- Feeding history:

- Breastmilk or formula or other?

- Frequency of feeds?

- If formula or expressed breast milk, what volume is being given?

- If breastfeeding, does Jane have any concerns about supply or any pain with feeding?

- Satiety post feed?

- Does Michaela become upset during a feed?

- Are there any other feeding concerns?

-

How is Michaela sleeping?

-

What do the days look like for Michaela and Jane?

-

What is the urine output?

-

What is the frequency and consistency of stools?

-

Any rash?

-

Any fever?

- General systems review

-

How is Jane coping?

-

What social supports do the parents have in place?

-

Any concerns of harm or injury to Michaela?

Neonatal examinations

A full neonatal examination should be performed with particular attention to growth measures (weight, height and head circumference which should all be plotted on an age and sex appropriate WHO chart), vital signs (temperature, HR, RR), alertness, skin perfusion, and any signs of non-accidental injury. Full head to toe examination should be completed including but not limited to neurological, ENT, cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal examinations.

Laboratory tests and radiographic examinations are usually unnecessary if the child is gaining weight normally, there are no red flags on history and a thorough physical examination has been performed which is all normal.

The examination itself may reassure the parents. It can be helpful to point out the normal examination findings to parents as you are going.

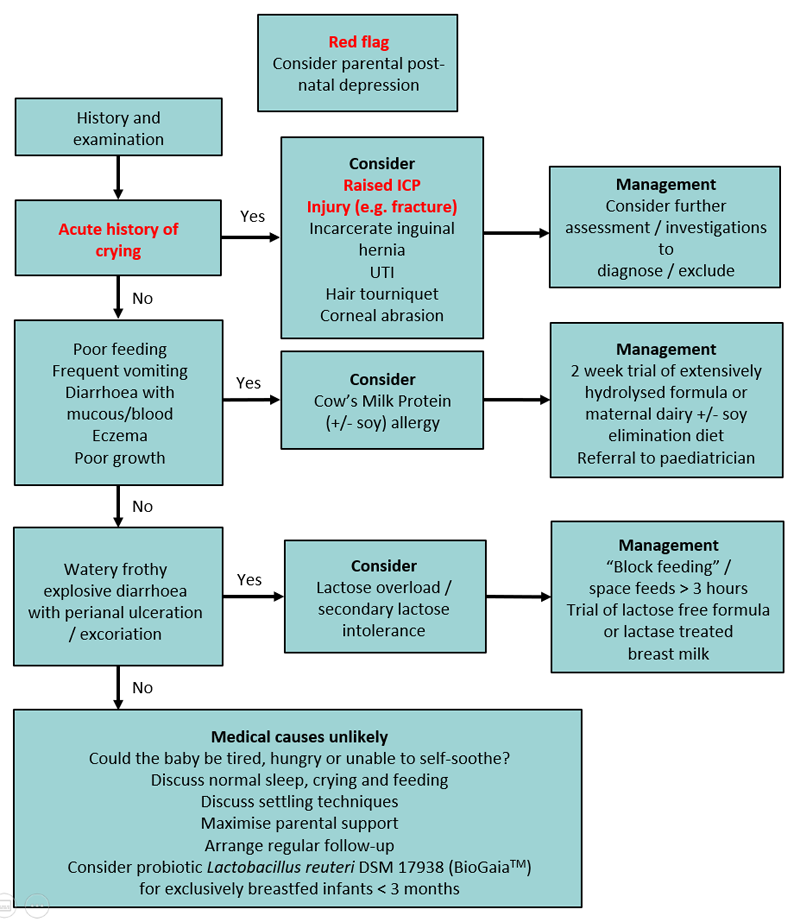

Medical causes of excessive crying

Pathological causes of crying include:

- CNS

- CNS abnormality (Chiari type I malformation)

- Infantile migraine

- Subdural hematoma

- Gastrointestinal

- Constipation

- Cow’s milk protein intolerance

- Lactose overload / malabsorption*

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) – no causal relationship has been established between GOR and infant crying. The presence of GORD is rare.

- Rectal fissure

- Incarcerated gastrointestinal hernia

- Pyloric stenosis

- Infection

- Meningitis

- Otitis media

- Urinary tract infection

- Viral illness

- Trauma

- Non-accidental injury

- Corneal abrasions

- Foreign body in the eye

- Fractured bone

- Hair tourniquet syndrome

Medication is rarely indicated.

*Note that primary congenital lactase deficiency is extremely rare.

- suspect if there is frothy watery diarrhoea generally from birth, often associated with perianal excoriation and failure to thrive

- diagnosis is made by the presence of faecal reducing substances ≥0.5%% and pH < 5.0, and confirmed by clinical response to lactose-free formula

- in breastfed babies, consider functional lactose overload (high lactose content in foremilk that overwhelms the baby’s lactase enzymes). This is NOT a lactase deficiency but a mismatch in the lactose load vs available lactase. It is generally seen when mum has a generous breastmilk supply leading to the baby filling up with the lactose rich foremilk and not reaching the creamier hindmilk. These babies may feed frequently, gain excessive weight, have frothy, explosive stools and pass excessive wind.

- in formula-fed babies, may be lactose malabsorption due to mucosal injury of the gastrointestinal tract secondary to cow milk / soy protein allergy

- if baby breastfed, block feeding (feeding from one breast over a period of time to downregulate supply) should be considered with the support of an experienced lactation consultant. This is generally a short term intervention and care should be taken not to induce mastitis or lead to under-supply. Parents should be reassured that functional lactose overload is not harmful to the baby and will not cause any damage to the GI tract.

- if baby formula-fed, consider trial of lactose-free formula although this is very rarely needed. If an alternative diagnosis such as cow milk protein allergy is suspected then an appropriate formula, such as an extensively-hydrolysed formula, should be recommended.

Non-pathological causes of crying

Common non-pathological causes of crying include:

- Hunger (suspect if weekly weight gains are below expected or even at lower end of normal spectrum)

- Feeding problems (fussing at the breast or bottle, back arching during feeds and feed refusal can be signs of positional instability, inadequate milk transfer, forced feeding and / or a negative association) – direct families to appropriate online resources or engage support of a lactation consultant if you are not confident in performing feeding assessment and advice

- Insufficient sensory input

All families need support and should be reviewed regularly until the crying settles.

A baby behaviour diary can help normalize the crying or help parents recognise patterns.

Management plan for Michaela

-

Refer Jane to ongoing support

(e.g. child health nurse, lactation consultant, unsettled baby clinic, inpatient mother and baby units)

See the 'Resources for parents' section for more information - Reassure that it is unlikely there is a pathological cause

for the crying

Spend time explaining how you have excluded pathological causes as this will provide reassurance

Ensure you elicit Jane’s specific concerns around the crying and address these

-

Encourage Jane to use a baby behaviour diary

Track Michaela’s crying and feeding patterns

Explain normal crying and sleep patterns and the normal trajectory of crying so that Jane understands what to expect -

Discuss strategies of dealing with excessive crying in babies

Provide printed information

Encourage Jane to experiment with a “toolbox” of strategies for managing the unsettled behaviour

This may include excluding reversible causes such as a dirty or wet nappy, being too hot or too cold or having a tag or clothing irritating her. Once these are excluded, encourage Jane to experiment with offering a feed or a change in sensory environment.

A change in sensory environment may include any of the senses eg cuddles, movement through rocking in arms or pram, warm bath, soothing noise, dummy or going outside -

Consider possible depression, anxiety and other mental health issues in the mother

The maternal and family psychosocial state must be taken into account as maternal post-natal depression may be a factor in presentation. Note that excessive crying is the most proximal risk factor for Shaken Baby Syndrome. Use validated screening tools e.g. Edinburgh perinatal depression screen. -

Ensure safety of Michaela and Jane

Assess risk of non-accidental injury (NAI) -

Arrange follow up

Assessing infants in an acute setting: History

- Feeding:

- How is baby fed (e.g. breast / bottle)?

- How much, How often?

- Is the baby just not interested or having difficulty?

- Nature of ‘distress’ and crying:

- Pattern/timing

- When did it start?

- Is the baby able to be settled?

- Wet nappies:

- How many?

- How wet?

- When was the last wet one?

- Alertness:

- Is the baby behaving normally?

- Waking for feeds?

- Difficult to rouse?

- Stools:

- Frequency

- Consistency

- Any major changes?

- Any other preceding changes e.g. recent urtis or fevers?

Assessing infants in an acute setting: Examination

- A full and thorough examination

- Examination of particular importance to Michaela includes:

- General assessment on baby’s alertness/lethargy/pallor

- Observations: Is Michaela showing signs of shock?

- Assessment of hydration: mucous membranes, fontanelles, skin turgor

- Abdominal examination: particularly looking/feeling for distension, masses, bowel sounds

Assessing acute distress in babies and young children

Assessment of acute distress in babies and young children can be very difficult.

Often it is a process of elimination and assessing red flags.

- Repeated examination is useful to look for the persistence or evolution of signs and evaluate response to treatment.

- Analgesia should be used and will not mask potentially serious causes of pain.

- Investigations are guided by the most likely cause. Most children need no investigations

- True bilious vomiting is dark green and warrants urgent surgical input.

Common causes of abdominal pain by age

Time critical illnesses are in red

| Neonates | Infants and Children |

|---|---|

| Hirschprung’s enterocolitis Incarcerated hernia Intussusception Irritable/unsettled infant Meckel’s diverticulum Necrotising enterocolitis Testicular torsion UTI Volvulus |

Appendicitis Abdominal trauma Constipation DKA Gastroenteritis Henoch Schonlein Purpura Incarcerated hernia Intussusception Meckel’s diverticulum Mesenteric adenitis Migraine Pneumonia Pyloric stenosis Testicular torsion UTI Volvulus |

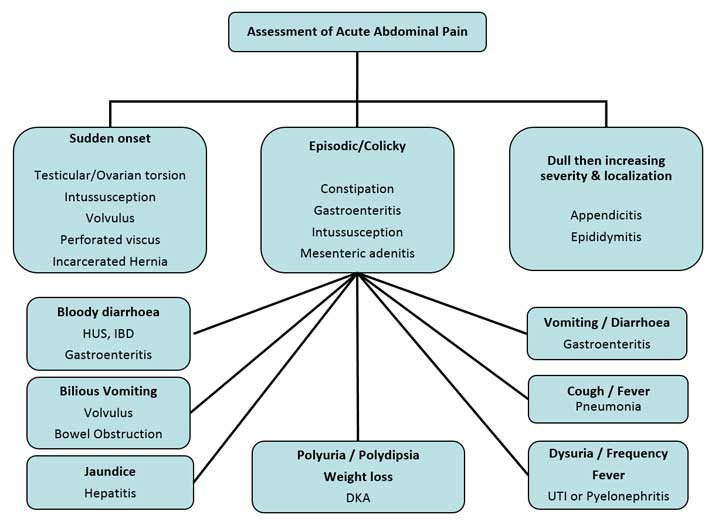

Assessment of acute abdominal pain - Symptoms and signs with associated differential diagnose

Management of a suspected intussusception

- Resuscitation: is there a need for a fluid bolus?

- IV access and fluid management

- See fluid management guidelines

- Pain management

- Child likely nil by mouth

- Initially for distressed baby intranasal fentanyl may be an option at 1-1.5microgram/kg

- Once IV access is obtained may consider IV opiates e.g. morphine (0.1mg/kg titrated to effect)

- Need to ensure that any child receiving analgesia that could cause sedation or respiratory depression need to be in an appropriately monitored environment

- Nasogastric tube

- Early transfer to a hospital with paediatric surgical capabilities

- Support the parents

Intussusception flowchart

Preparing infants for transfer

Given Michaela is a young baby with a potentially life threatening, time-critical diagnosis it is likely that she will be retrieved as a priority. It is still possible that, depending on location and current retrieval workload, she may be in your hospital for several hours.

By starting preparation for transfer you will save precious time on ground and a speedier arrival at the destination hospital.

- Retrieval Services/Central Coordination will be able to offer paediatric specialist (ED/ICU/Anaesthetist) advice in regards to management whilst awaiting transfer. The specialist team at the destination hospital may also have advice/requests for initial management.

- Michaela will be nil by mouth so will need to continue fluid management via IV therapy.

- Once you have addressed any deficit or resuscitation required you should calculate her ongoing fluid requirements based on her weight.

- Consider total required therapy for the time frame of the transfer until the child arrives at the destination hospital (i.e. you don’t want the fluid bag to run out mid transfer).

- IV access in the paediatric population can be difficult and traumatic for the child, the parents and you, the doctor. It is imperative that the IV is secured well and well looked after. This is of particular importance for transfer and the retrieval team will greatly appreciate a well secured IV.

- Pain management

- Antiemetic

- Consider need for a prophylactic antiemetic

- Temperature management

- Parent / support person

- In the paediatric population a parent or support person will often transfer with the child, if there is likely to be a delay before retrieval often it’s a great idea to have a family member bring in a small amount of personal belongings/phone charger etc. Don’t let the parent/s leave though, there’s nothing worse than an unexpectedly quick retrieval and a parent missing in action.